Written by Suchitra Marti for Michael Filtz’s Explorations in Cinema & Communications course.

In examining the collective, the artist’s role significantly impacts how we view our reality, a fact long used by vanguards to inspire revolutionary thought. As filmmaking became particularly accessible, this form has transformed into a powerful tool of resistance. As imperial exploitation reigned, revolutionary filmmakers found new ways to protect and preserve the laurels of their artistic resistance. Thus, “Third Cinema” originated as a Latin American film movement taking liberatory action against the neocolonial stronghold in many South American nations. Rooted in the Marxist tradition, this movement has consistently challenged traditional narratives of filmmaking and has redefined art as more than entertainment, interconnecting with liberation movements across the world as an important intersection of art and politics.

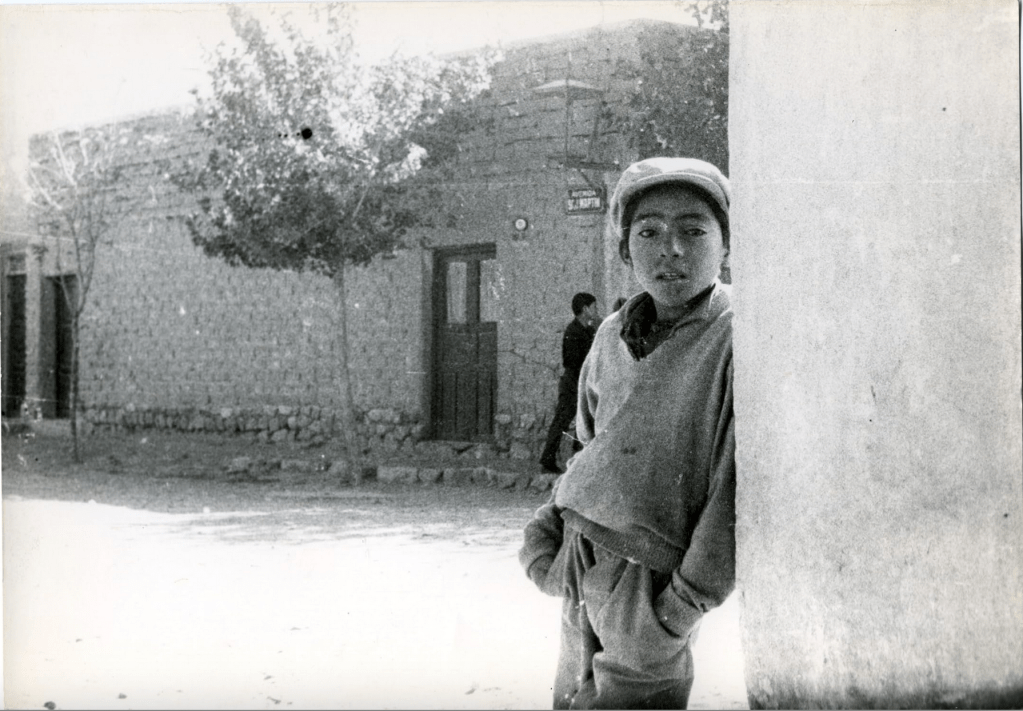

In Latin America, the 1960s and 1970s emerged as a time of revolution. While many nations had gained independence, colonial narratives and imperialist powers still had a strong influence over economic and societal structures across much of the global south. As Cold War tensions raged on, the US became increasingly adamant on stopping the spread of Marxist ideas. For example, the 1959 Cuban Revolution, consolidating Fidel Castro’s power, increased the United States’ scrutiny over the region while providing inspiration to neighbouring nations. Yet, US interventionism prevented many of these nations from sustaining their socialist governments. Production of explicitly political cinema emerged in the 1950s, most popularly in Cuba (Fernando Birri as referenced by Sarto in Chasqui), reinforcing resistance and ideas of revolution. As a need for change reverberated across Latin America, filmmakers began creating political pieces as a manifestation of radicalization and cultural transformation, cinema created for the people, by the people. They sought to create films which reflected their needs and identities, an experience which bourgeois cinema could not depict. Following his seminal Black God, White Devil (1964), Glauber Rocha, a pioneer of the Brazilian “Cinema Novo” details that “it is not a single film but an evolving complex of films that will make the public aware of its own misery” (The Aesthetics of Hunger). One of four foundational manifestos, “The Aesthetics of Hunger” was followed by perhaps the most significant text of Third Cinema “Towards a Third Cinema” by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, detailing the essence of the movement and its necessity in a revolutionary setting. They define First Cinema as most mainstream, Hollywood-esque, stating that “until recently, film had been synonymous with show or amusement: in a word, it was one more consumer good” (Getino, Solanas, 108). The next level, Second Cinema, allows the auteur to express themselves without the imposing, mainstream, structures, “but such attempts have already reached, or are about the reach, the outer limits of what the system permits” (120). Lastly, they express Third Cinema as “making films that the system cannot assimilate, and which are foreign to its needs or making films that directly and explicitly set out to fight the system” (120). In essence, the manifesto was a call to subversion. It transformed the audience member as a passive observer, to one who could transform history. It did not adhere to any technique and favoured the filmmaker’s own exploration but recommended a guerilla-style handheld filmmaking. This cinema was not documentation, it was a revolutionary act: “(…) it sought its own liberation in the subordination and insertion in the others, the principal protagonists of life” (130).

The first film explicitly coined under the term Third Cinema was in fact Solanas and Getino’s three-part La Hora de los Hornos (1968) (The Hour of Furnaces) which detailed class hegemony in and around Argentina during a time of media censorship. The first part, “Neocolonialism and Violence”, blends current and archival footage detailing the realities of the working-class. The film’s introduction is of colonial history with a focus on the trick-loan signed with the Baring Brothers Bank in 1824. The audio is often an overlay of the narrator and audio from the scene, creating powerful depictions of reality: “But will the colonizer ever admit that the blood of the man he has colonized is the same as his?” (La Hora de Los Hornos). The distribution of the film was clandestine, often with underground screenings with aid from armed revolutionaries. In 1969, it was finally screened at the Festival of Vina del Mar in Chile with a large student audience (Mestman). The screenings increased student demonstrations and encouraged explicit praxis within various fields (Getino, Solanas). Political cinema began to spread in the global south with the release of films such as Antonio Das Mortes (1969) and Xala (1975).

A milestone in political cinema was reached with the Third World Filmmakers Conference in Algiers in 1976. It was the first time on a global stage that “Third World” films were given a platform without repression, seeing the presence of notable filmmakers such as Fernando Birri and Ousmane Sembene. The central conversation surrounded the condemnation of imperialism and the importance of bringing the people’s cinema to the forefront (Black Camera 163). It incited the creation of the Third World Cinema Office to strengthen relations between “Third World” filmmakers and ensured financial support and secure outlets for guerilla style cinema (165). Organization of these conferences grew with two the following year (Buenos Aires and Montreal).

The 1980s saw a revival of Third Cinema principles especially with innovation in African documentary films: “Along such lines, early African filmmakers, including Sembène, preferred “documentarized fictions” for non-documentary films to offset early Western ethnographic documentaries that depicted Africa as static non evolving” (Thackway and Téno 19). This gave rise to filmmakers such as Jean Marie Téno who drew inspiration from earlier filmmakers such as Ousmane Sembene. In 1992, he released Afrique, Je Te Plumerai (Africa, I Will Fleece You) to depict the withstanding colonial structures of Cameroon, the only African nation colonized by three imperialist powers: Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The film embodies many stylistic choices of this revision, combining both documentary scenes and fabricated scene stagings (as in the set, not content). The film begins with an open letter to President Biya by Celestin Monga, condemning his policies: “What is this ‘law-abiding nation’ where an obscure politician can lock up anyone without accountability?” (Afrique, Je Te Plumerai). The most well expanded segment details the state of literature in Cameroon and the dependence of bookstores and libraries on foreign publications: “With the death of literature, comes the demise of reflection leading to the end of our collective memory” (Afrique Je Te Plumerai). This is contained within a series of interviews conducted by Marie Claire Dati with local booksellers, librarians, and publishing houses. This reflects the more traditional style of socio-documentaries. Like many other liberatory films, it also includes archival footage of newsreels depicting a colonized Cameroon and testimonies from writers, journalists, and union members. However, Téno then cuts back to his childhood; he revisits the moment he fell in love with film. This recreation reflects the exploration of stylistic choices beyond the documentary, giving a personal insight into the subject matter. In addition, the film includes symbolic elements, even throughout the documented portions. The use of the lark is heavy, tied back to the French children’s song “Alouette.” The lark serves as a metaphor for imperialist exploitation, stripping African nations of their resources for personal profit: “Their song became a lament that often could be heard late into the night” (Afrique Je Te Plumerai).

Into the 21st century, executing the principles of Third Cinema became much easier. The development of technology allowed a much larger segment of the population to explore their filmmaking capabilities. Political cinema has become much more large-scale with filmmakers openly denouncing institutions on the global stage. With the rise of social media, real time content has generally become easier to access. In 2023, a young filmmaker named Bisan Owda began sharing her journey and her experience under the Gaza genocide and the Israeli occupation. With only a camera, she has captured months while denouncing the Israeli government. In 2024, her documentary It’s Bisan from Gaza and I’m Still Alive received an Emmy nomination but not without major backlash from pro-Israeli groups. She has faced countless opposition from those who wish to silence her, including the Israeli government who is known to target journalists, yet she remains committed to revealing the truth (It’s Bisan from Gaza and I’m Still Alive). While her work is not specifically classifiable under Third Cinema, it echoes the many sentiments of resistance and the subversion of traditional media norms. Thus, while the films of the 21st century have somewhat diverged from the original ideas of Solanas and Getino in terms of distribution and style, they remain true to the spirit of questioning and transforming our reality. In understanding all that Third Cinema and its descendants have to offer, it is imperative to remember that liberation is a collective front, with unwavering belief that a better world is near.