Written by Dorothée Gingras-Bernardin for Magdalena Olszanowski’s Cinema and Communications: Selected Topics course

Winner of the Cheryl Simon Writing Award for Subtext’s Fall 2024 issue

Is it possible to perceive nature without projecting human values onto it? How can cinema reinforce our anthropocentric mentality or, on the contrary, contribute to a reconceptualization of nature and animals? Through their exploration of anthropocentrism, the documentary films Grizzly Man by Werner Herzog (2005) and La Pieuvre by Jean Painlevé (1928) offer reflections surrounding these questions. Despite their wildly different styles and eras of production, these two films form a complementary duo. While Grizzly Man criticises and deconstructs a widespread anthropocentric mentality, La Pieuvre proposes a representation of animals outside of the confines of anthropocentrism. Ultimately, these two films argue that claiming mastery over animals leads to greater misunderstanding, whereas distancing the human perspective from the animal in front of the camera leads to a greater acceptance and appreciation of what they are: unpredictable, impenetrable, and, above all, awe-inspiring.

Anthropocentrism is defined as the assumption that humans have a superior intrinsic value to nature and animals. This ethical viewpoint justifies the use of nature as a tool for humans; as a means to an end. A common human tendency derived from anthropocentrism is anthropomorphism: the tendency to attribute human characteristics to animals (Cahill 74).

These concepts are at the core of Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man. The film demonstrates the pervasiveness of anthropocentrism, even in the context of animal activism. This found footage documentary presents the viewpoints of two individuals: Timothy Treadwell, a wildlife activist who spent multiple summers living with grizzly bears and documenting his experience, and Werner Herzog, who edited and narrated Treadwell’s footage. Throughout the film, we discover an eccentric protagonist, an outcast, who devoted his life to changing the public’s fearful attitudes toward grizzly bears. Herzog is not apathetic to Treadwell’s convictions, yet he introduces the idea that Treadwell’s activism might serve his own interests more than the animals, suggesting that he never truly understood the bears. By using non-linear editing, Herzog offers a commentary on humans’ saviour complex and their desire to exert control over nature.

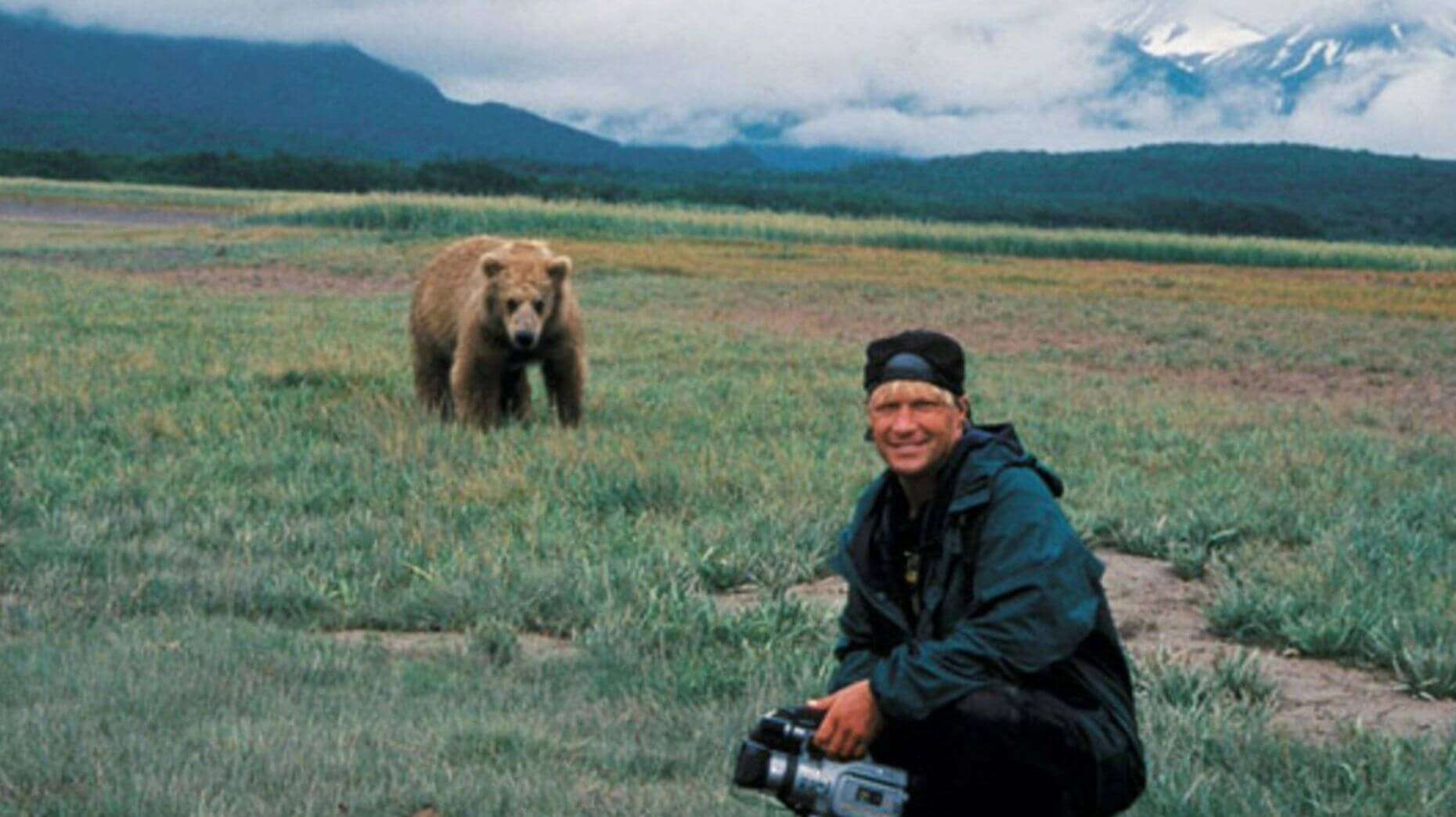

Throughout the film, Timothy lives in close proximity with the grizzly bears. He swims with them, pets them, and gives them names, like “Mr. Chocolate” or “Tabitha.” He acknowledges their danger, but believes that he has become “one of theirs” (Herzog 00:24:34 – 58). For Timothy, other humans, including the Parks Service employees, constitute a threat to the bears and would be unable to survive in the bears’ habitat. In a moment of great exaltation, he says to the camera, “Come here and camp here […] you will die, you will die here. They will get you. I found a way to survive with them. I’m just different and I love these bears enough to do it right. And I’m edgy enough, I’m tough enough. This is it, this is my life. This is my land!” (Herzog 1:34:00 – 43). Treadwell’s confident belief that he understands the bears and his portrayal of them as tameable creatures is deconstructed by Herzog. The filmmaker underlines the many ways in which Treadwell’s understanding of animals is tinted by his limited human perspective.

Firstly, this is done through non-linear storytelling, which Herzog uses to recontextualize the footage. Even when watching seemingly inoffensive footage of Treadwell swimming with the bears or playing with them, viewers are incited to be critical of his perception since they know something he does not: he will eventually be eaten alive by one of them. His claim of understanding the animals therefore becomes subject to the viewer’s scepticism. Herzog further emphasises this effect through editing. In the first scene of the film, a bear points its muzzle a few inches away from the camera and Treadwell’s hand reaches out to pet it. Herzog sets the tone by introducing a dynamic, hopeful guitar tune in the background. However, when the bear suddenly leaps dangerously close to the camera, the music abruptly cuts and we hear Treadwell’s heavy breathing as the bear walks away. Herzog creates a stark contrast between the friendly, playful bears that Treadwell believes he knows and their unpredictability.

As the film goes on, it becomes evident that the bond Treadwell claims to have with the bears relies on the projection of his human values onto them. For instance, after a fight occurred between two male bears competing for the attention of a female, Treadwell describes the scene as “so violent, so upsetting,” and “extremely powerful, extremely emotional” (Herzog 00:57:17 – 58:38). Later on, he also relates the bears’ behaviour to his own romantic experiences with women. In this scene, he gives these wild animals human intentions and downplays the instinctive survival factors that lead them to fight for procreation. Treadwell exhibits a common form of anthropomorphism: projecting human values onto animals to explain behaviours that are morally repugnant to humans (“Anthropo. and Its Vicissitudes” 74). The violence he witnessed, despite being fairly common in the natural world, upset him. He immediately attempted to find humanity in the bears and justify their actions through sentiments that he could see himself experiencing. Not only can this lead to a misinterpretation of the animals, but also reinforces the idea that humans need to recognize “equivalent rational capacities” in animals to be able to respect them (Khan 14).

Herzog demonstrates that by failing to rise above the anthropocentric mentality that is so prevalent in our culture, Treadwell caused harm to himself and the cause he was defending. Herzog highlights how Alaska’s Native communities have historically coexisted harmoniously with the bears. In an interview with Herzog, an Alutiq man, conservator of Kodiak’s Alutiq museum, says, “If I look at it from my culture, Timothy Treadwell crossed a boundary that we have lived with for seven-hundred years […] Where I grew up, the bears avoid us and we avoid them” (Herzog 00:28:53–30:15). In his opinion, what Treadwell viewed as wildlife conservationism was, in fact, an invasion of the bears’ territory that “did more damage to the bears than [good]” (Herzog 00:30:00). Ignoring Native Peoples’ established mode of respectful cohabitation with the bears, Treadwell decided to get closer to the object of his fascination. Although his affection for bears appeared to be sincere, Treadwell used nature and wildlife as a backdrop for his personal quest of finding himself, casting himself as a hero.

Moreover, Treadwell’s self-directed mise-en-scène reflects this saviour mentality. Treadwell often places himself in the foreground of the shots, thus occupying most of the visual space he claims is intended for the bears. This becomes symbolic of Treadwell’s intrusion into the bears’ habitat. Some of Herzog’s editing choices also underline the performative nature of Treadwell’s character. For instance, Treadwell performs a speech about the threat that the Parks Services and other “human invaders” pose to him and the bears. Where Treadwell clearly intended to edit the footage, Herzog decided not to make any cuts; leaving a two-minute uninterrupted take of Treadwell mumbling insults to himself and restarting his speech several times with an increasingly dramatic tone. It becomes abundantly clear that this adventure was answering to a need to present himself as heroic, fearless, and in control. Treadwell sees himself as “edgy enough”, “tough enough,” shouting, “This is it, this is my life. This is my land!” (Herzog 1:34:00–43). These moments are more than a comedic choice; they underline the invasive nature of his endeavour and reflect colonial and patriarchal ideals.

Contrastingly, Jean Painlevé, director of La Pieuvre, suggests that there is a fundamental divide and misunderstanding between animals and humans due to the omnipresence of anthropocentric beliefs: “Constantly swinging between anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism, [humans] are incapable of understanding an animal that does not remain within the field determined by these two blinders” (Zoological Surrealism 81). Painlevé’s diagnosis is reminiscent of the protagonist’s mentality in Grizzly Man. Painlevé’s work is both attempting to represent animals beyond the confines of anthropocentrism and acknowledging the fact that human bias will never entirely disappear.

Unlike Treadwell’s footage, La Pieuvre is much aware of the trap of anthropocentrism. With a simple cinematographic style, featuring long, uninterrupted shots and microcinema techniques, Painlevé creates a film that is more ecocentric. His documentary is atypical in its approach, which can be described as both scientific and poetic. Indeed, dramatic, contemplative shots of the octopuses are interspaced with title cards with anatomical facts. The combination of these two styles is very conducive to ecocinema. Indeed, through the scientific representation of the animal, the viewer gains an objective, biological understanding of it. The contemplative, artistic representation of the animal encourages the viewer to admire its beauty. Rather than being guided by the voice of a narrator who interprets the animal’s behaviour through their own human perception, the viewers wander between the known and the unknown. Contrary to Treadwell, Painlevé does not try to make the audience relate to the octopus or believe it understands it. Instead, Painlevé focuses on the animal’s movements and unique textures, confronting the viewer with its non-human nature.

At the beginning of the film, the octopus is seen from a distance and from conventional angles; the animal is recognizable, familiar. A shot of the octopus’ eye is followed by a title card that reads, “An open eye, very human” (Painlevé 04:40). This ironic statement alludes to the viewer’s presumed anthropomorphic tendencies. Are humans really the only ones to possess eyes? The audience becomes aware, critical of its perception of nature. As the film progresses, the camera gets closer to the octopus, showcasing the intricate details of its body. In a particularly striking shot, the octopus’s syphon sucks in water before ejecting it. Its rhythmic movements are mesmerising, exuding a strange, otherworldly grace. Painlevé does not seek to humanise the animal. Instead, he captures its movements so closely that he is able to “unsettle the grounds by which comparisons between species and humans are made” (Zoological Surrealism 25).

The comparison between Timothy Treadwell’s and Jean Painlevé’s filmmakings highlight the ways in which cinematic techniques can be used to reframe our perception of nature. Treadwell’s desire to understand and relate to the bears ultimately translates into their anthropomorphic representation. Conversely, Painlevé depicts an appreciation of the enigmatic and unfamiliar nature of animals. The distance that is established between the human viewer and the animals on screen is crucial in avoiding an anthropocentric portrayal. However, binary thinking can also be quite dangerous; While anthropomorphism contributes to the reinforcement of human supremacy, viewing animals as radically separate from humans can result in a similar conclusion. The question then arises: How can we redefine ourselves outside of the human-animal binary?

Works Cited

Boonpromkul, Phacharawan. “Of Grizzlies and Man: Watching Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Through an Ecocritical Lens.” Manusya: Journal of Humanities, vol. 18, no.2, Jan. 2015, pp. 28-43, doi.org/10.1163/26659077-01802002.

Cahill, James Leo. “Anthropomorphism and Its Vicissitudes: Reflections on Homme-sick Cinema.” Screening Nature: Cinema beyond the Human, edited by Anat Pick and Guinevere Narraway, Berghahn Books, 2013, pp. 73-90, doi.org/10.1515/9781800732957-007.

Cahill, James Leo. Zoological Surrealism: The Nonhuman Cinema of Jean Painlevé. University of Minnesota Press, 2019. JSTOR, doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvc16n5t.

Fateminasab, Seyedreza. “The Monsters of Nature: Representation of Environmental Ethics in Cinema.” Community Change, vol. 3, no. 1, May 2020, pp. 1-3, doi.org/10.21061/cc.v3i1.a.26.

Herzog, Werner, director. Grizzly Man. Lionsgate, 2005. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=efNtliiyT3M

Khan, Ciannait. “Anthropocentric Paradoxes in Cinema.” Journal of Critical Animal Studies, vol. 18, no.2, 2021, pp. 5-41, journalforcriticalanimalstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/JCAS-Vol-18-Iss-2-May-2021-FINAL.pdf#page=8.

Painlevé, Jean, director. La Pieuvre. 1928. Willoquet-Maricondi, Paula, editor. Framing the World: Explorations in Ecocriticism and Film. University of Virginia Press, 2010. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wrgnd.