Written by Dorothée Gingras-B for Magdalena Olszanowski’s Ecocinema course

Through grim images of factory chimneys, opaque fumes, and behemoth infrastructure, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1964 drama Red Desert tells the story of a woman’s growing sense of alienation and disorientation in the face of a highly industrialized and increasingly polluted environment. In the midst of Italy’s booming after-war industrialization, Giuliana (Monica Vitti), the wife of the manager of an Italian power plant, attempts to find a sense of stability. After getting hit by a truck and hospitalized, she grapples with a persistent case of neurosis, which only seems heightened by her polluted and impersonal environment. Through mundane scenes of Giulianna’s life—visiting her husband at the factory, spending time with friends in a fishing cabin, walking through decaying landscapes—Antonioni depicts the distress of a woman who is misadapted to the large-scale mechanization of her environment. Through his mise-en-scène and sound design, which are heavy in symbolism, Antonioni masterfully interweaves a narrative of environmental exploitation with the human experience of alienation.

By establishing a strong contrast between the comfort of personal spaces and the harshness of the industrial space through mise-en-scène and sound, the film establishes a sense of empathy for Giulianna; the viewer can notice elements of the industrial sphere infiltrate personal spaces and, like Giulianna, can begin to perceive the threat they represent. The first portion of the film, in which Giulianna visits her husband at the power plant, is polluted by loud, incessant roaring from the machinery, drowning out the dialogue almost entirely. The discomfort is only heightened by the unpredictability and hostility of her surroundings; outside, black dust covers the dying vegetation, and tall chimneys release yellow smoke into the grey sky.

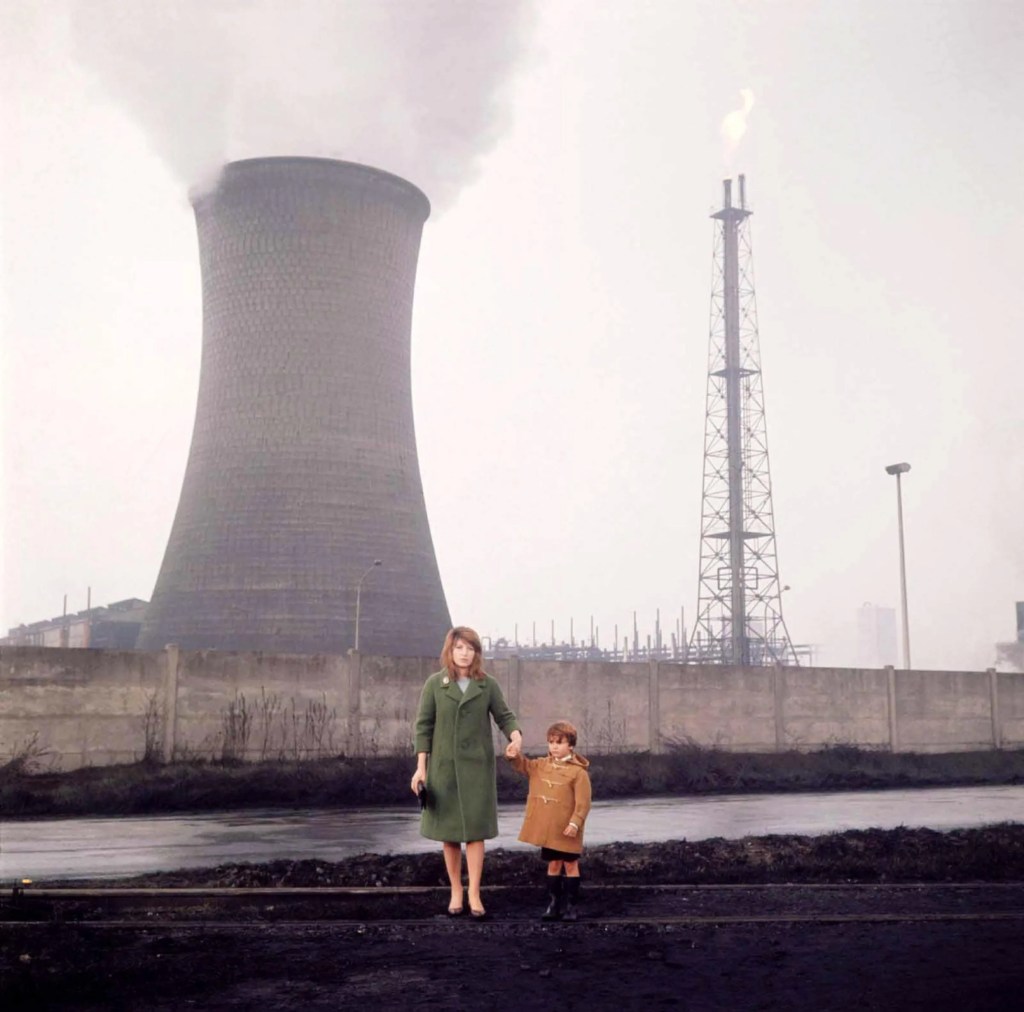

Red Desert (Antonioni, 1964)

Inside the factory, clouds of smoke erupt at every turn, threatening to engulf her. In this jungle of pipes and motors, Giulianna seems particularly disoriented and fragile. As a viewer, we understand, even share her anxiety, unlike the people around her. The factory workers seem acclimatized to this environment. This aggressive chaos finally fades when she returns to the peaceful environment of her home. When she awakens in the middle of the night, the dark house, with its white walls, carpeted floors and minimalistic decor, creates a drastic contrast with the previous environment. We feel sheltered from the noise. The silence, however, only lasts a few short seconds. Giulianna begins to hear a faint remnant of a machine’s rumble, like tinnitus, in the stillness of the house. She leaves her bed and finds, in the darkness of her son’s bedroom, the source of the disruption: a toy robot rolling back and forth next to the sleeping child. This seemingly insignificant occurrence feels ominous; the unbearable sound of machinery has infiltrated the soothing silence of her home. The robot and its ceaseless activity inevitably evoke the factory with its mechanized and depersonalized environment. There is also a deep discordance between the image of the robot, evoking the idea of automatization, dehumanization and even excessive and self-destructive human ambition, and that of the mother watching her child sleep peacefully, evoking innocence as well as the precious and deeply human connection between a mother and her child. This striking juxtaposition expresses how radically opposed the external world and Giuliana’s personal world are. It thus becomes easier to understand how the infiltration of the industrial into her personal space is so threatening.

Throughout the film, Antonioni further uses the contrast between interior and exterior space to represent alienation and connection, notably when Giulianna visits her friends at the fishing cabin. Similarly to her house, the cabin acts as a shelter from the outside environment. The enclosed, warm space of the cabin, its red walls, and the crackling fire in the furnace create a stark contrast with the dark, polluted water and endless barren landscape that exist outside. The physical proximity to the people inside and the genuine connection Giulianna shares with them make this space a deeply personal one and create a scene that visually and narratively differs from the rest of the film. In the factory scenes, the employees work in disproportionately large spaces where they are far from one another. Some of the most striking shots of the film play with the contrast in dimensions between the behemoth industrial structures and the characters, who seem dwarfed and isolated within the frame. This sense of disconnect and isolation is completely reversed in the cabin scene, where the characters are laughing and lying atop each other in shots that are framed tighter. It is one of the few moments where Giulianna does not appear disoriented or agitated. However, her anxiety quickly returns as she looks through the window of the cabin and sees a massive cargo ship docking right next to them. The thunderous horn of the ship becomes louder as it approaches, and its black hull slowly obscures the window. This ominous arrival alarms Giulianna, who urges everyone to leave the cabin. The young adults, who only moments ago were laughing together in the warm cocoon of the cabin, now find themselves in the cold outside air, standing apart from each other. From Giulianna’s perspective, we see an opaque cloud of fog slowly engulfing them—an illustration of the danger that pollution poses to human life and, more subtly, an allegory for the alienation brought about by industrialization.

Red Desert (Antonioni, 1964)

In fact, as the film illustrates, the lack of true human connection is a symptom and a cause of mass industrialization. In one of the most evocative scenes of the film, a man who has to abandon his house because of pollution from a nearby factory talks with another man, who says, “Sometimes, I feel like I have no right to be where I am” (Antonioni, 00:38:57). While it enriches and empowers some, the exploitation of the environment leaves less space for others to live. This candid statement also expresses how the operations of these powerful corporations can affect individuals in the most private spheres of their lives, even making them feel like they do not belong in private spaces.

Despite being almost sixty years old, this film is extremely contemporary in the way it looks at the impacts of industrialization and environmental destruction on the human psyche. In many ways, Red Desert resembles Chloe Zhao’s Oscar-winning film, Nomadland (2020), which explores a similar narrative, but from a contemporary, North American perspective. Both films explore themes of alienation, industrialization, and pollution through poetic visuals that emphasize the isolation of the characters within the vast environment they inhabit. Still, the precision and sensibility with which Antonioni grasped a problem that his society had not yet fully experienced, make Red Desert a unique masterpiece.

Works Cited

Antonioni, Michelangelo, director. Red Desert. Performance by Monica Vitti. Film Duemila, 1964.