A comparative analysis of Miriam Toews’ Women Talking and Greta Gerwig’s Little Women

By Kara Chevry, written for Louise Slater’s Women and Anger course

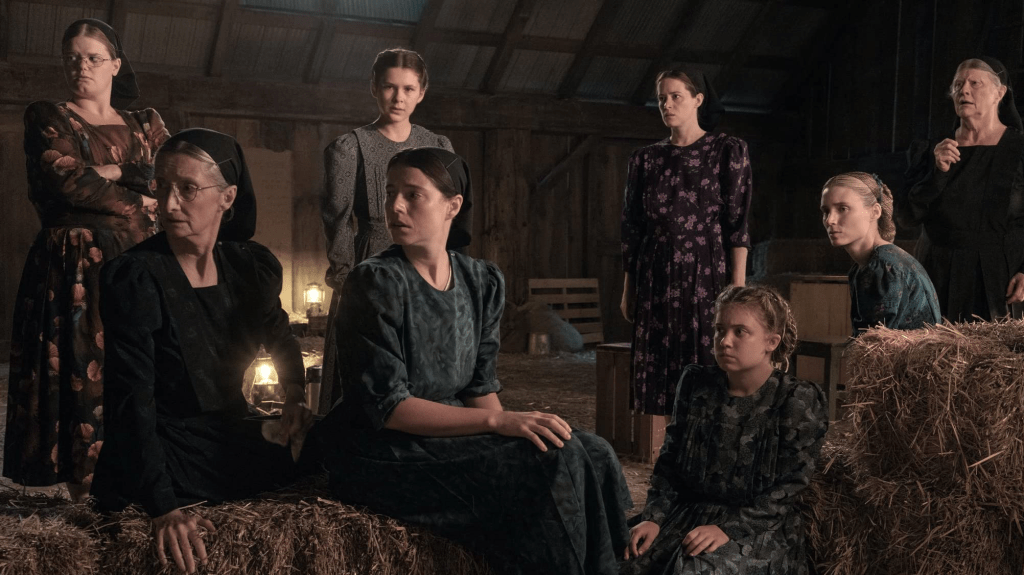

For four years, several women and girls within a remote Mennonite colony have woken up in pain and agony, their skin marked with bruises and cuts. The colony’s religious leaders laid the blame on Satan and his demons, but the truth would later be revealed when a woman witnesses a shadow lurking around her bedroom, carrying a jug of belladonna spray. Instead of Satan, the lurking shadows were men of the Molotschna colony caught drugging and raping over three hundred women and young girls. While the men face trial for their crimes, the Friesen and Loewen families have 48 hours to decide on behalf of the women of Molotschna whether they should stay and fight or abandon the colony altogether. Miriam Toews’ Women Talking reveals how oppressive structures like gender roles hinder women’s path to self-determination.

While pondering a Philippians Bible verse asking for the meaning of what is good, Ona concludes, “Freedom is good and better than slavery […]. And hope for the unknown is good, better than hatred of the familiar” (Toews 106). Because freedom is impossible while one is enslaved, it is clear to the reader that the wisest course of action for the women of Molotschna is to flee. If freedom and autonomy are synonymous, how can the women be autonomous as slaves to their brothers and spouses? When Agata says, “Imagine my hens telling me to turn around and leave the premises when I show up to gather the eggs” (Toews 116), through her sarcasm, she makes the implication that the women are treated like hens, whose only duty is to reproduce. Furthermore, when Mariche suggests that the women, “as members of the colony,” should protect the men if the court finds them innocent, Salome exclaims, “We’re not members! We are the women of Molotschna.” She explains that Molotschna is founded upon a system of male domination whereby women live out their days as “mute, submissive, and obedient servants” (Toews 120). As slaves and servants to Molotschna, they are not active members of society; instead, their autonomy is taken away and their sole purpose is to obey and comply with social expectations.

Additionally, because they are exclusively taught Plautdietsch, a language used by all Mennonites, the women are unable to interpret the Bible for themselves. As they consider whether leaving the colony will violate the Bible’s command that wives submit to their husbands, Mejal interjects; “We, the women, do not know exactly what is in the Bible, being unable to read it. Furthermore, the only reason we feel the need to submit to our husbands is because our husbands have told us that the Bible decrees it” (Toews 157). Their self-determination is further restricted by the fact that women are denied the right to read and write. As language is a tool that defines and reflects one’s worldview, stripping someone of their language is stripping them of their own worldview. When the men of Molotschna impose their language and their interpretation of the Bible, they impose their own cultural norms, beliefs, and values. In this case, language is used as a tool for domination. This means that if they leave, the women would not know how to communicate in the outside world. Language is vital to their survival and freedom, yet they have been robbed of it. Despite this theft, the women maintain their capacity for deep, complex, and rational thinking and are able to express their desires. They even draft a manifesto, clearly outlining the kind of society they wish to live in. They can now define what self-determination means to them, which encompasses the desire to protect their children, to keep their faith, and to think for themselves.

Due to patriarchal structures and gendered norms, women often experience conflict between pursuing their own personal ambitions and fulfilling societies’ expectations. This conflict is a significant barrier for the March sisters in Greta Gerwig’s 2019 Little Women. Set during the nineteenth century, the four March sisters navigate gendered social conventions and expectations of marriage as young American women of a lower class background.

In nineteenth-century America, marriage was considered the most important thing for a woman to do. As the March family faces poverty, the sisters are expected to marry wealthy men in order to support themselves and their families. While visiting her Aunt March, Jo reveals her intentions to defy social norms and make her own way in the world. Aunt March replies, “No one makes their own way, not really, least of all a woman. You’ll need to marry well” (Gerwig, 35:13–48). She agrees that the only way to be an unmarried woman is to be rich. During a conversation with Laurie, Amy speaks of marriage being an economic proposition. She says, “And if I had my own money, which I don’t, that money would belong to my husband the moment we got married” (Gerwig, 1:05:20–06:22). The March sisters – as do the women of Molotschna – recognize that the patriarchal institution of marriage does not allow women to be in control of their own lives and ambitions. In truth, 1860s marriage laws guaranteed that married women would be financially dependent on their husbands through a legal doctrine that erased her independent legal status and merged it with her husband’s. All of her personal property then belonged to and was managed by her husband (Basch 347). The doctrine of marital unity declared a wife should give her husband control over both her property and her person (Ziegler 65). As a wife, her duties would involve taking care of his home, providing him with exclusive access to her body, and bearing their many children (Ziegler 65). According to historian Norma Basch, English jurists’ justified this legal doctrine because “in the eyes of the law” the husband and wife are considered one person: the husband (Basch 347).

Additionally, many women began to reject the institution of marriage because they found that it interfered with female autonomy, self-development, and achievement (Berend 935). In previous centuries, mutual affection sufficed between husband and wife. However, by the late nineteenth century, love took over as the only legitimate foundation of marriage. Young people were encouraged to marry someone they loved, rather than someone they could learn to love (Berend 937). She disregards his financial status and marries him because she truly loves him. On the other hand, Jo turns down Laurie’s marriage proposal. She says, “I can’t say ‘yes’ truly so I won’t say it at all” (Gerwig, 1:36:30–38:04). She chooses not to marry him because she doesn’t love him in a romantic way. While Jo was initially determined to stay single and free, she later announces her desire to be loved as she realizes that marriage is not solely an economic proposition.

She says about women, “And I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for […]. But I’m so lonely.” (Gerwig, 1:42:20–43:00). Despite Jo’s change of heart, it still rings true that while marrying Laurie was the right thing to do economically, Jo was simply not in love. Although Jo and Meg have vastly different dreams in life, they both conceptualize marriage beyond the preservation of gender roles and instead adopt a philosophy prioritizing romantic love as a means to spiritual fulfillment. This revolutionary concept parallels Ona’s proposal that the women of Molotschna should pursue “a new religion, extrapolated from the old, but focused on love” (Toews 56). She disregards his financial status and marries him because she truly loves him. On the other hand, Jo turns down Laurie’s marriage proposal. She says, “I can’t say ‘yes’ truly so I won’t say it at all” (Gerwig, 1:36:30–38:04). She chooses not to marry him because she doesn’t love him in a romantic way. While Jo was initially determined to stay single and free, she later announces her desire to be loved as she realizes that marriage is not solely an economic proposition. She says about women, “And I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for […]. But I’m so lonely.” (Gerwig, 1:42:20–43:00). Despite Jo’s change of heart, it still rings true that while marrying Laurie was the right thing to do economically, Jo was simply not in love. Although Jo and Meg have vastly different dreams in life, they both conceptualize marriage beyond the preservation of gender roles and instead adopt a philosophy prioritizing romantic love as a means to spiritual fulfillment. This revolutionary concept parallels Ona’s proposal that the women of Molotschna should pursue “a new religion, extrapolated from the old, but focused on love” (Toews 56).

In conclusion, the March sisters and the women of Molotschna both struggle against patriarchal structures tied to women’s labor, reproduction, strict gender roles, the institution of marriage, and society in general. As women’s personal interests and desires are devalued by these structures, they are often left to choose between self-determination and economic necessity or between freedom and love. Both groups are acutely aware of the manipulative forces that dominate their lives and force them to follow a specific path. In the face of such manipulation and exploitation, they grasp that these forces are agents of the patriarchy. They conceptualize new definitions of love and freedom and can now determine what they truly desire, independent of male authority. In the end, all women want is to think for themselves and to have choice rather than control.

Works Cited

Basch, Norma. “Invisible Women: The Legal Fiction of Marital Unity in Nineteenth-Century America.” Feminist Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, 1979, pp. 346–66. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/3177600

Berend, Zsuzsa. “‘The Best or None!’ Spinsterhood in Nineteenth-Century New England.” Journal of Social History, vol. 33, no. 4, 2000, pp. 935–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3789171

Gerwig, Greta, director. Little Women. Sony Pictures Entertainment Motion Picture Group, 2019.

Toews, Miriam. Women Talking. Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.