By Alexandrina Sandu, written for Cheryl Simon’s Film Theory course

Andrew Higson, professor of Film and Television at the University of York, explains that it is primordial “[…] to pay attention to historical shifts in the construction of nationhood and national identity: nationhood is always an image constructed under particular conditions” (Higson 44). Considering that cinema is a tool through which national identity can be expressed, it is then only fair to take into account the different events that redefined the national identity of a country when exploring the country’s national cinema. In fact, it would be hard not to and would probably simplify national cinema as representing all films made in a specific country. Thus, to properly comprehend the German cinema of the late 60s to the early 80s, otherwise known as the New German Cinema or the Young German Cinema, we ought to do just that: analyse it in relation to the changing national identity that occurred in Germany during its first post-war decades.

Important to German Cinema is the concept of the Heimat which describes “a felt relationship enduring over time between human beings and places that can extend metaphorically to connote identification with family or nation, cultural tradition, local dialect or native tongue” (Eigler and Kugele 34). In other words, it generally implies that the German land constitutes an essential part of the German self. Throughout Germany’s film history, it has been used and adapted to the fluctuating German identity, while also serving different political agendas such as that of the Nazis’ (Von Moltke 3-4). In the 1950s, the Heimat was repurposed, this time “as an amnesia-inducing blanket that covered the horrors and guilt with kitschy, romantic Alpine movies” (Bittner).

Die Fischerin vom Bodensee, 1956

The decade was indeed saturated with Heimatfilme. The trademarks of these films include German landscapes, moral men, girlish women, love stories, firm values inherited from the past, as well as German folk traditions and festivities (Von Moltke 23). To a German society that was coming out of a radical political and social climate and that was thus in search of a new national identity, these films offered a simple and reassuring conception of a new possible German identity; one rooted in German traditions and values, one that was seemingly not damaged by the fascist era. The Heimatfilme were also the product of a film industry that turned inward in an effort to assert itself in a market dominated by American films. The industry implemented a protectionist strategy which was “pursued deliberately through vertical integration and resistance to foreign imports” (Von Moltke 23). Overall, the Heimatfilme offered a very restricted and traditional image of the German population which prevented the industry from innovating and the population from dealing with the recent past. Ultimately, the era “yielded no significant auteurs […] and produced hardly a stylistic experiment worth mentioning” (Von Moltke 21).

However, at the beginning of the 1960s, the Heimatfilme were reaching their end, losing legitimacy as tensions between generations were growing (Loewy). The youth was discontented with what they deemed to be a shallow German cinema of the 1950s that did not address important contemporary issues, the recent past, nor the social climate of their society (Frey 19). They indeed believed that there had been “no true caesura, no ‘Zero Hour’ in 1945; a more or less submerged Nazism still existed” and was noticeable, for instance, in the strict parenting style and education of the youth (Frey 19). Consequently, a desire to rebrand the German identity and the one displayed in films arised. In 1962, young filmmakers signed the Oberhausen Manifesto which called “for an alternative German cinematic production to supersede the industrial and aesthetic traditions” of the last decade, particularly of the Heimatfilme (Kapczynski 305).

The struggles the New German Cinema encountered were not, however, limited to unfavorable policies. The movement was indeed also met with hostility from German audiences. Its unpopularity was due “to its refusal to take audience’s need for entertainment seriously, to its noncommercial bent, and to its penchant for ambiguous narrative structure” (Sinha). Although throughout the seventies the New German Cinema adapted to the needs of German audiences by shifting towards the production of narrative-orientated films, the themes tackled by the movement were ones that “provoked, angered, and challenged its audiences” (Rentschler 8). Instead of neglecting social issues and the recent past as did the Heimatfilme, these new films made those topics central to their plots. Bold and explicit explorations of race, gender, class, identity, alienation, radical politics, American cultural colonialism, fascism, education, and family, which painted the German society as damaged and problematic, were forced upon German audiences who had become accustomed to the reassuring and purified national identity of Heimatfilme (Sinah).

As Higson argues, however, it is the role of national cinema “to pull together diverse and contradictory discourses, to articulate a contradictory unity” (Higson 44). By bringing counter-narratives to the table, the New German Cinema did just that: it expanded Germany’s national cinema, thus demonstrating that national identity is not homogenous.

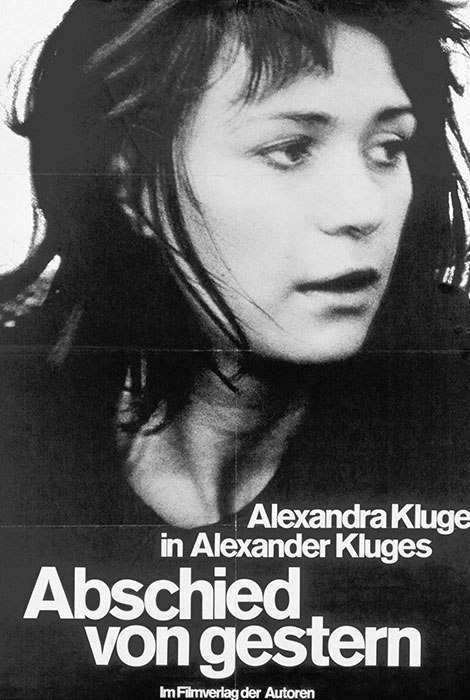

But the New German Cinema would not truly begin until the late sixties when, with the formation of the Board of Young German Film in 1965, interest-free loans would begin to be given to promising young directors who desired to create films free from conventions. This prompted the production of the first film of the movement: Alexander Kluge’s Yesterday Girl (1966). Yet, since the Board was funded by the government, the commercial film industry felt it was threatened. It therefore demanded a revision of governmental policies, leading to the creation of the Film Promotion Act in 1968. Although the Board continued to function, this new law ensured commercial films were granted virtually all governmental subsidies, making it hard for the young directors of the New German Cinema to obtain financing. It was not until the early seventies, with The Film and Television Agreement (1974), which allocated 34 million marks for film productions between 1974 and 1978, that the film movement truly set off (Sinha).

Alice in the Cities (1974)

Taking a closer look at Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) and Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities (1974), two films by key filmmakers of the New German Cinema, reveals the ways in which the aforementioned themes were discussed by the movement. Fassbinder’s film is a bold criticism of the ubiquitous racism found in German society. The film follows the relationship between Emmi, a German woman, and Ali, a Moroccan immigrant worker. As the story unfolds, Emmi is confronted with the hostility of her friends, family, and neighbors as they learn she is romantically involved with an immigrant who is also much younger than her. As such, Fassbinder is displaying his society’s racist rage, subverting the idea that the fascist period and its extreme ideologies only belonged to the past. Furthermore, by displaying Emmi’s own problematic attitude towards Ali, such as asking him to show his muscles to her friends, Fassbinder underlines that racism was so institutionalised in Germany that even the most alert to social injustices were likely to have internalized racist assumptions and behaviors. In Wenders’ film, issues of alienation and loss of identity in an era of globalization are explored. The film follows Philip, a journalist, and Alice, a young girl whose care Philip has been entrusted with. The two hit the road in search of Alice’s grandmother, whom Philip plans to leave Alice with. Yet, the film ends without them finding her. Untimely, the only sense of belonging either of them find is within their friendship. The impossibility for them to find a home on the German land, both literally and figuratively, undermines the idea promulgated by the Heimatfilme that the German self is safe and at home in Germany.

In conclusion, the New German Cinema appeared in reaction to the Heimatfilme of the 1950s. Although its rise in popularity did not happen instantaneously, the movement persisted. Explorations of controversial and contemporary issues made the New German Cinema an important addition to Germany’s national cinema as it presented a German society not yet seen on the screens.

Works Cited

Bittner, Jochen. “Why the World Should Learn to Say ‘Heimat’.” The New York Times, 28 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/28/opinion/america-heimat-germany-politics.html

Eigler, Friederike, and Jens Kugele. “Introduction: Heimat at the Intersection of Memory and Space.” De Gruyter, 2012, doi.org/10.1515/9783110292060.1

Higson, Andrew. “The Concept of National Cinema.” Screen, vol. 30, no. 4, 1 Oct. 1989, pp.36–47, doi.org/10.1093/screen/30.4.36

Kapczynski, Jennifer. “Postwar Ghosts: ‘Heimatfilm’ and the Specter of Male Violence. Returning to the Scene of the Crime.” German Studies Review, vol. 33, no. 2, May 2010, pp. 305–30.

Loewy, Hanno. “Contes tragiques, Heimatfilme ou mélodrames? Les générations allemandes et l’Holocauste.” Questions de Communication, vol. 4, no. 2, Sept. 2003, pp. 343–64.

Frey, Mattias. “Rebirth of a Nation.” Postwall German Cinema History, Film History and Cinephilia, Berghahn Books, 2013.

Rentschler, Eric. “American Friends and New German Cinema: Patterns of Reception.” New German Critique, no. 24/25, Oct. 1981, pp 7-35, doi.org/10.2307/488041

Sinha, Amresh. “Same Old New German Cinema, on Julia Knight’s New German Cinema: Images of a Generation.” Film-Philosophy, vol. 9, no. 2, May 2005.

Von Moltke, Johannes. “No Place Like Home : Locations of Heimat in German Cinema.” University of California Press, 2005.